It’s all a big mess when you really look at it and try to think about it. There’s this big pile of maybe evidence from 1979 to 1988, a story that’s all literally in pieces, artifacts, and a good deal that’s less than artifacts, call them leavings. How is anyone to make sense of this?

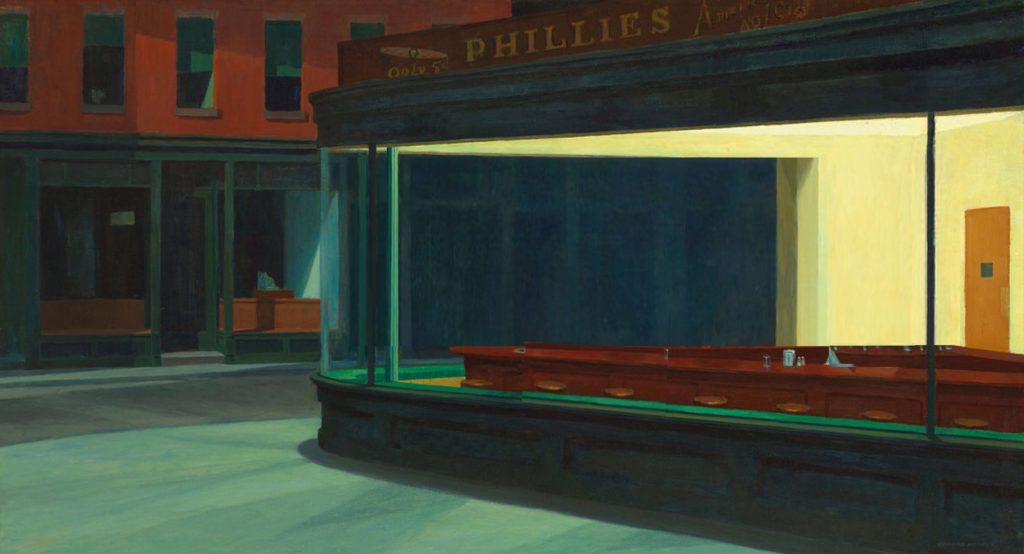

There’s a real place.

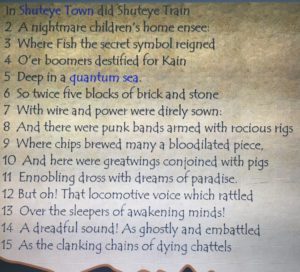

There’s a mysterious subculture twisted from a children’s poem.

There was a plot of sorts:

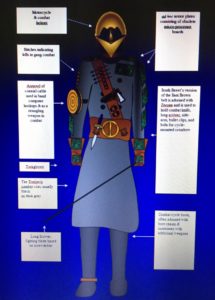

They did their work with tools they stole and tools they made:

Personal Weapons

Silent Urban Assault Bikes

Custom Writing Input Instruments

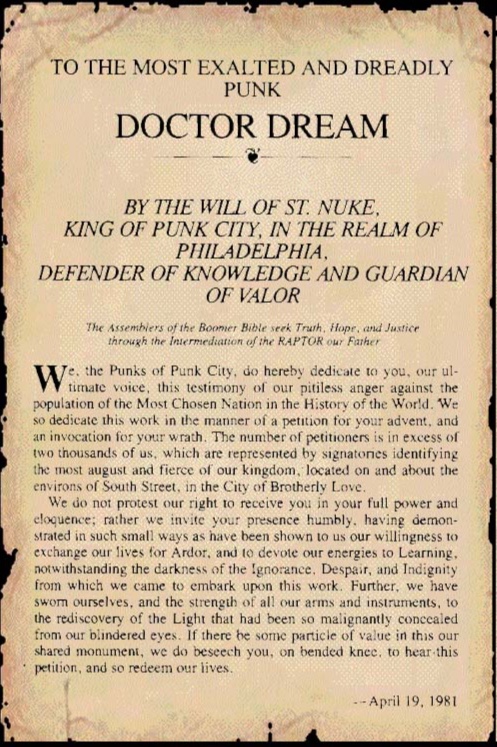

They had their own Mission Statement…

…Duly signed by all.

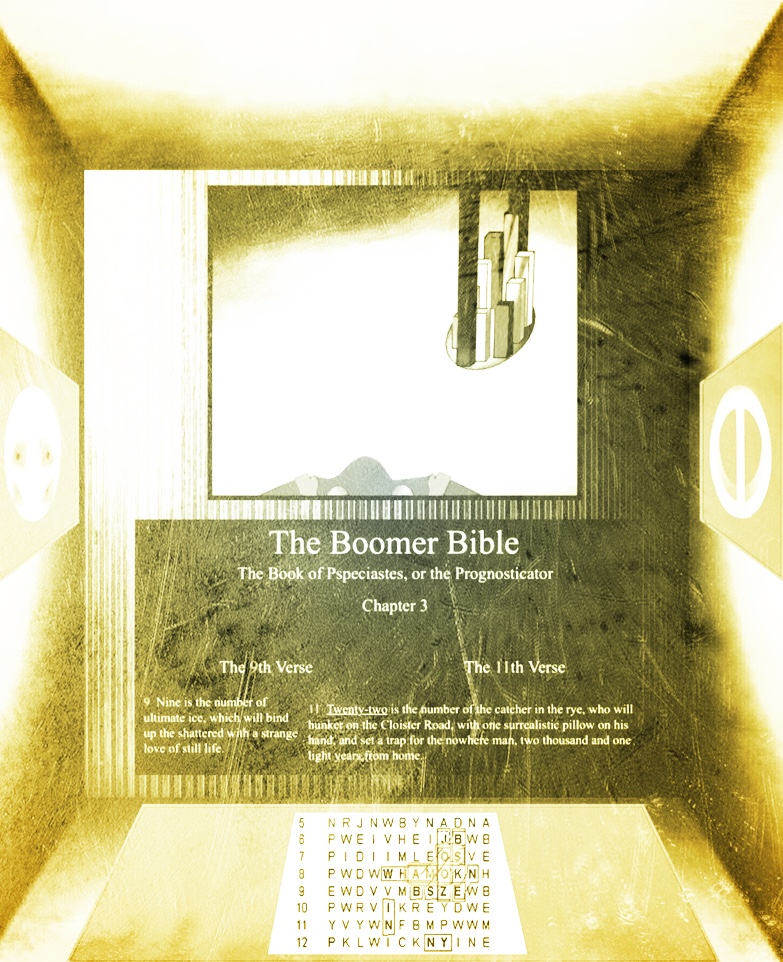

They had their own religion.

Their Own Tarot Deck (for plotting)

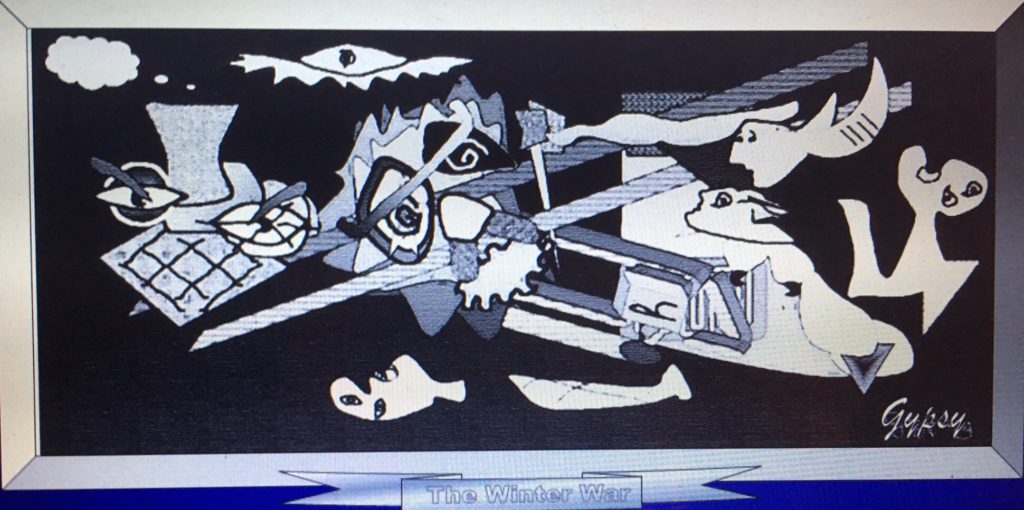

They had their own art.

And they had a Vanishing Act in May 1985 that left everyone in the dark.

But then there were artifacts, dug from the urban underworld in the thaw of 1987.

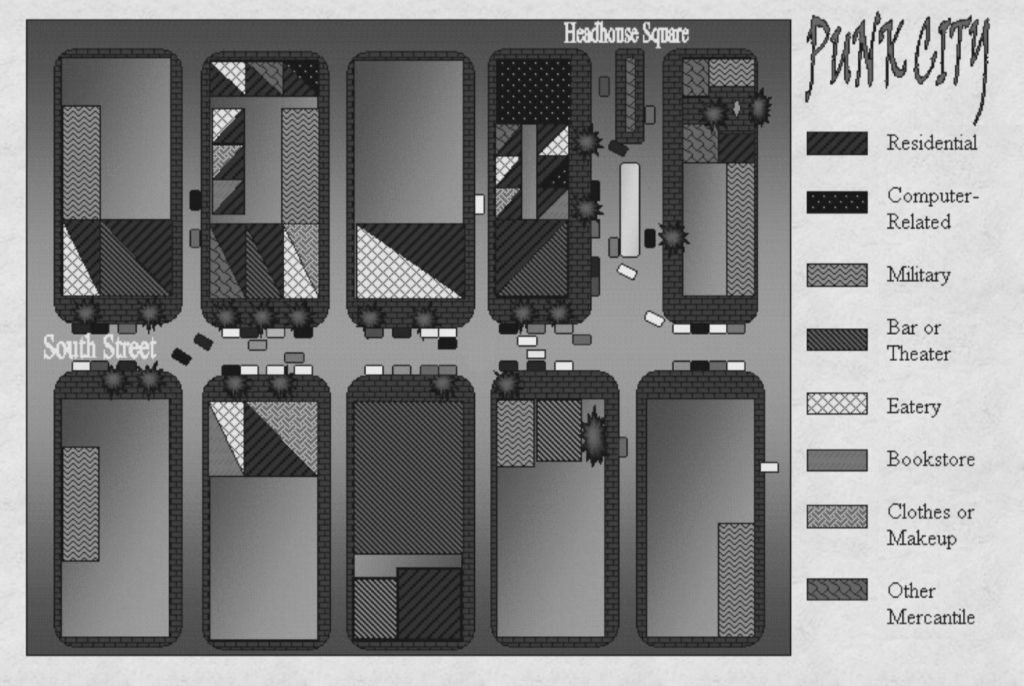

Maps

Weapons & ammunition

Bikes & parts

Computers & Parts

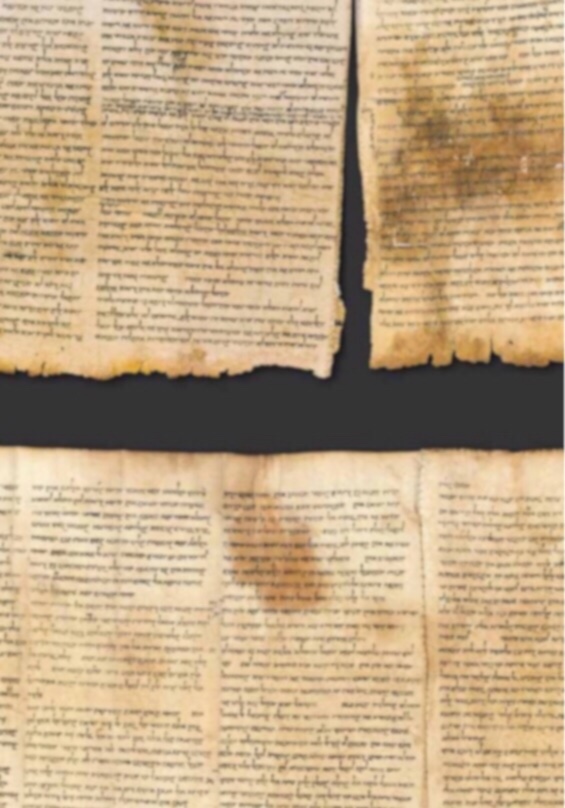

Manuscript Fragments

Shrines…

…And Predictions?

Bones

Now what are we supposed to think? When in doubt, we are informed by our culture to seek out the experts, the professors and objective investigators who can look at the evidence and tell us whether something big happened and we missed it, or nothing much happened but the usual tidal wave of rumors and meaningless garbage. That’s why we’re so fortunate to be able to read this particular book on the subject of the Punk Writers of South Street and see if there isn’t some rational way out of this imbroglio.

In approaching the lives and works of punk writers, one is almost immediately faced with such an unprecedented profusion of obtrusive and potentially primal elements of all kinds—seminal, definitional, conformational, and transformational—that the task of distinguishing significant from merely incidental influences requires an extraordinarily meticulous and objective methodology.

It is for this reason that a much more than cursory knowledge of punk’s formative milieu must serve as a prerequisite to the study of punk works. Any reader not mindful of the myriad circumstances attendant on the emergence of this phenomenon runs a double risk: first, of misreading its confused but all too literal fragments of self-history as profound but difficult literary inventions; and second, of inferring from this quite spurious aura of profundity a wholly erroneous schema of punk intent, in which ineptitude is interpreted as technique, confession as metaphor, and brutality as philosophy.

And for those who would approach the subject despite these risks, there is yet another obstacle to surmount, one of such magnitude that any scholar who encounters it could almost be pardoned for concluding that punk’s manifold mysteries are beyond hope of resolution. The nature of this formidable stumbling block was ably described by Clausen in one of the first (and only) essays written on the punk writer phenomenon:

The punks do not publish their works. They may perform them on stage, paint them on the walls of public buildings, or force them on pedestrians at knifepoint, but it is anathema to their code to submit them to publishing houses for dissemination to the world at large. Nor are they in the least disposed to discuss themselves or their work, insisting that whatever reasons they have for writing, the desire to communicate is not one of them.

These are primary anomalies, and the demise of the punk writing movement has altered the situation only for the worse. The writings that were difficult for Clausen to acquire in 1982 are still not widely available, and present evidence indicates that a high percentage of them may have been lost altogether in the fifteen years since the movement’s end. Moreover, the rigid code of silence observed by most of punk’s principals and followers when punk writing was in its ascendancy has not been abandoned but has rather been fiercely retained, almost as if it had become a kind of sacred relic to those who mourn punk’s passing.

In the face of such daunting obstacles, the question inevitably arises: Are the potential benefits of scholarly inquiry into the punk movement worth the labors that will undoubtedly be involved in penetrating its mysteries? Assuredly, any scholar who did not pose this question would be derelict in his/her duty to both his/her profession and his/her peers, notwithstanding the generous latitude society at large has traditionally granted the academic community in the matter of deciding which subjects are worth of investigation and which are not. Simple pragmatism demands that members of the academic community concur, willingly or regretfully, with the opinion expressed by Lieberman in his celebrated Treatise on Modern Criticism that “There is more of wistfulness than wisdom in the credo Homo sum: humani nil a me alienum puto.”

Thus, we confront the task of determining whether or not there is prima facie evidence that punk writing does not merit serious study. And some would argue—indeed, some have already argued—that such evidence abounds. It must be admitted at the outset, for example, that punk writing is, almost without exception, bad writing. No less tolerant and distinguished a critic than Jameson wrote the following indictment:

Even at its putative best, punk prose is repetitive, strident, deliberately offensive in tone and technique, and quite devoid of that most vital prerequisite of literature, the writer’s interest in—and sympathy for—his or her characters. At its worst, punk prose is beneath contempt, consisting of little more than illiterate and incoherent diatribes full of mixed metaphors, fragmented constructs of plot and thought, and irrational unregenerate hostility.

What can there be in all this to attract serious scholarly interest? This is a vital question and one that must be addressed at some length, but having posed it in its proper place, I must at once beg leave to defer discussion of it until such time as the groundwork has been laid for a satisfactory answer, whose referent elements would necessarily at present include facts and conclusions not yet available—for confirmation or disputation—to my readers. Precipitate consideration of such issues could have no reasonable prospect of allaying an only too prudent skepticism. I therefore propose, with apologies to the ordinally minded among you, to lay the foundation for an informed decision by describing some of the punk writing movement’s background and history. Much of the information that follows was obtained from secondary sources, but this is an unfortunate necessity whose potential ill effects I have attempted to minimize by using only that material for which at least circumstantial supporting evidence could be obtained. In those few instances here included for which no such supporting evidence could be found, I have provided the identity of my source so that others can verify or disprove their testimony independently. All speculations in the following summary have been, I believe, expressly identified as such.

Herewith, I offer a brief overview of the punk writing movement, beginning with what is known of its origins.

The Beginning

In the fall of 1978 an unemployed auto mechanic named Samuel Dealey moved from the small town in southern New Jersey where he had been born to the South Street section of Philadelphia. A week later he wrote a letter to his sister describing his new home and his reasons for moving there:

…there’s plenty of kids & nobody to mes with you’s, if I want to gets boozed up I do, theres plenty places for that. Nobody saying hey you, do this, do that where was you yestiday. Its all free here I can dress how I like and I got a place with some other guys who know some of the realy cool bands here, a guy called Eddy Pig is learning me the gitar, so dont worry I’ll be making some good bread soon…

Dealey’s characterization of the South Street atmosphere was not an exaggeration, but a fairly accurate description of what had lately become a Mecca for culturally and economically dispossessed young people. The “realy cool bands,” moreover, were such a presence in the area that in May 1979, residents in neighboring Society Hill twice petitioned the Philadelphia Police Department to enforce the local noise ordinances more strictly, citing “repeated late night disturbances by punk rock bands whose exceptionally loud music and riotous behavior have become an intolerable nuisance to everyone in the vicinity.”

Despite these pleas, however, the police were apparently unable to impose order on the burgeoning population of South Street rebels. According to some contemporary accounts, the police were actually afraid of the punks, and by the fall of 1979, a de facto state of anarchy gave young people the freedom to do whatever they wished as long as they remained within the confines of a ten-block strip known as Punk City. Dealey, meanwhile, had joined a band called ‘The V-8s’ and, having changed his name to Johnny Dodge, was struggling to attain some kind of renown in the punk hierarchy. “I’m going to be somebody,” he wrote his sister. “I’m more punk than anybody here ever thought of.”

As confident as Dealey may have been about his prospects for punk stardom, the slightly defensive tone of the latter statement suggests that he was already finding it difficult to attract attention in what was essentially a leaderless, standardless culture. Too, he may have been discovering that the music itself was too lacking in substance to provide him with a platform for his ego. From its inception, punk music in the U.S. had been suffering from a debilitating identity crisis, as music scholar Roy Keller observed in a 1981 essay on the subject:

(It was) an offshoot of traditional rock and roll that if clear about the sartorial requirements it imposed on its adherents was hopelessly unclear about either its purpose or direction. Unable to agree on so simple a matter as whether punk music represented a reaction against, or a fulfillment of, the cultural imperatives of rock and roll, punk musicians took refuge in mere outrage, competing with one another on and off stage for top honors in boorishness and hostility.

It was at this juncture that a wholly unexpected element intruded on the heretofore closed world of Punk City. What direction Dealey might have taken had he never met Percy Gale, we can only surmise; what is certain is that in November 1979, Dealey formed a brief alliance with Gale that resulted in a cross-pollination between punk and computer technology, which in turn gave birth to the entire punk writing movement.

To comprehend the significance of the event, we must extend our scope of interest twenty miles northwest, to a region near the Pennsylvania Turnpike nicknamed Semi-Conductor Strip, where numerous high technology firms were competing for survival in the volatile market for computer hardware and software.. It was here that a brilliant electronics engineer named Percy Gale had been employed for three years by Neodata Corporation, a firm that produced word processing systems for the corporate market.

Gale’s career was progressing well, by all accounts, and he had recently been promoted to vice president in charge of new product development when Neodata’s founder, a young enfant terrible named Tod Mercado, launched a lengthy campaign to acquire Monomax Corporation, then the fourth largest computer company in the world. The takeover fight was one of the bloodiest on record and when the dust had settled in late 1979, Mercado assumed nominal control of a consolidated NeoMax Corporation which was so deeply in debt and so divided in its top ranks that Wall Street analysts doubted its ability to make prudent business decisions. Accusations and law suits were rife, and dethroned Monomax executives insisted in print that Mercado had completed the acquisition through the use of illegal tactics and unsavory sources of funding.

Soon after finalization of the acquisition, Gale resigned from the new corporation and moved to South Street, allegedly to escape the stress of corporate life. It is impossible to prove that Gale had any purpose other than curing a case of burnout. But there is plenty of anecdotal evidence that Gale was, in fact, a close personal friend of Tod Mercado, and in light of subsequent events, it seems possible that he resigned from NeoMax either to escape questioning about his knowledge of acquisition-related events or, more intriguingly, to pursue some secret project he had dreamt up with his boy wunderkind boss.

I hasten to add that there is no documentation of any such project.

There is, however, a mass of hearsay evidence that there existed some connection between Mercado and the punk writers of South Street. Almost all contemporary accounts confirm this directly or by implication, which represents an interesting exception to the norm among chroniclers of Punk City, who seem to differ sharply on many of the most basic ‘facts’ they report on. But whether Percy Gale’s presence on South Street was the by-product or the source of Mercado’s punk connection, we may never learn to a certainty. For example, the very same accounts which verify Mercado’s communications with punk writers tend to characterize Gale in starkly different ways. Under the sobriquet ‘The Sandman,’ he is in various accounts lionized as a major figure, depicted as a gifted though narrow technological guru, and dismissed as a minor supporting player, a kind of informed onlooker. The perspective on Gale adopted by any given chronicler of punk history seems to hinge on the very same issues that confront the scholar, which is to say that one’s view of Gale’s role and importance is determined by the particular assumptions one makes about what punk writing was and what it may have meant, if anything.

All we can say with confidence is that for whatever reason, Gale left a well paying corporate position, as well as an opulent suburban townhouse in King of Prussia, to move into a decaying urban neighborhood, where he participated in founding the phenomenon known as punk writing.

Boz Baker’s highly personal—and somewhat questionable—memoir, “The Razor-Slashing Hate-Screaming De-Zeezing Ka-Killing, Doctor-Dreaming Kountdown,” contains a passing mention of the first meeting between Dealey and Gale, but the only authentic record I have been able to locate is a reference in another of Dealey’s letters to his sister, in which he writes:

…Met a computer guy at Gobb’s said he could fix some hi teck effects for the band. Sounded like too much bread to me but he says unless I wanted to learn the gitar for real (I never claimed I was no Hendricks did I) I should give it a try, don’t worry about the bread til we get to it. Said I’d see him around mabe we’d talk later. Mabe he’s crazy but mabe not too, who knows.</blockquote/>

Dealey must have overcome his doubts about Gale because he began collaborating with him almost immediately and soon departed from the V-8s to form his own band, Johnny Dodge & the 440s, which gave its first performance on November 27, 1979, at a South Street bar called the Slaughtered Pig….

YOU’ll FIND THE CONTINUATION OF THIS BOOK IN “PUNK CITY” at Amazon.com.