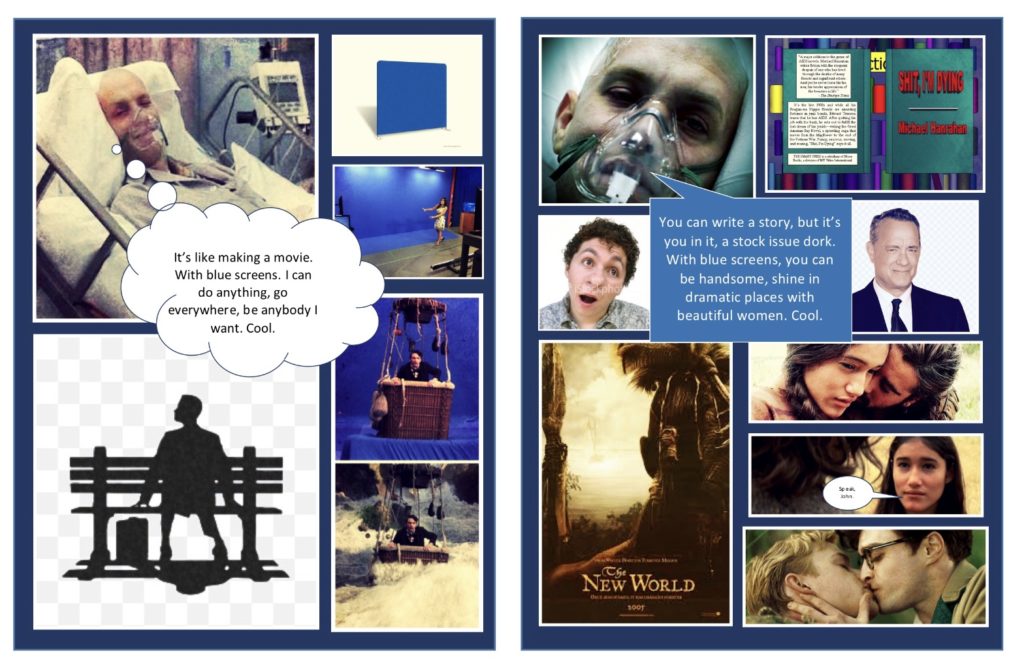

In the movie “Job and the Volcano,” six time Oscar Winner Tom Banks starts feeling sick at his job in Philadelphia, no wonder, and goes to see a doctor, resulting in the scene above. His first response is probably a lot like yours or mine would be. He writes a novel about his rotten luck, using the nom de guerre Michael Hanrahan.

Hell to get AIDS. But a great way to get on the bestseller list. I could get lucky. Ask my ghostwriter. Get it?

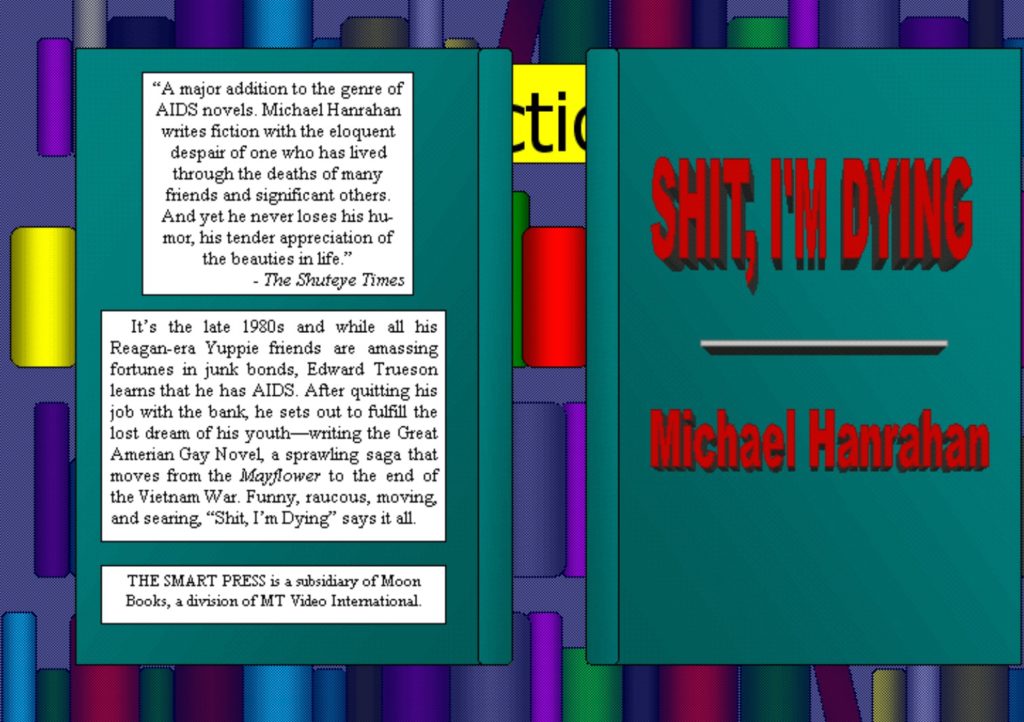

Shit, I’m Dying

Chapter One

I was getting restless. Bill Boggs was a friend from the days so long ago—exactly three weeks now—when I was also a broker, furiously peddling thick sheaves of paper that promised millions if the sky didn’t fall in. But the sky had fallen in, on me at least, and I knew I shouldn’t have shown such an early draft of my work to a straight, even one I liked as much as Bill.

“The thing is,” Bill said, the way the straights do, as if there were only one ‘thing,’ and they had it in the back pocket of their blue suit-pants, “You guys always seem to think that everybody famous was gay. It’s just not convincing.”

I reread the passage he was so riled up about.

“Speak for yourself, John,” murmured Pocohantas. She was a drab girl who continuously exuded a strong smell of deer meat. John Smith edged farther away from her. He didn’t want that scent of rotting venison on his suit with Miles Standish coming so soon for a visit. No, what he wanted was Miles Standish himself—and not in the company of this young woman, but alone, where he could sound out the possibility so subtly alluded to in their discourse, the possibility which had kept him awake nights dreaming of…

“John.” Pocohantas was patient but insistent.

“John! Don’t you have anything to say to me?”

He turned back to her from his fevered imaginings. “Yes. I do. I feel you should know that buckskin is passé. It is no longer la mode. Do I make myself clear?”

“Yes, John.” And then she smiled that damned secret smile of hers, as if she knew. She didn’t know shit.

“It’s that last sentence, isn’t it?” I asked. “John Smith wouldn’t have said ‘didn’t know shit.’ You’re right. I’ll change it.”

Bill stood up, ready to return to the safe environs of his bulls and bears. “Sure,” he said. “That’ll take care of it. I’m glad to see you looking so healthy and energetic.”

“You don’t like my novel,” I said suddenly. A storm cloud I hadn’t seen coming was upon me, black and bursting with lightning, rain, and fury. “It just isn’t possible to you that we have always been around, right in the middle of things, keeping this big secret from all you dull, conventional, heterosexual mediocrities. You spend a big chunk of your lives trying not to see us at all, pretending we’re not there, and you get so good at lying to yourselves that you start thinking it’s some kind of modern fad that’s confined to a few streets and bars in New York and San Francisco. And that’s exactly the kind of narrow-minded, bigoted, delusional, bullshit myopia I’m trying to expose with my novel. And what’s more,” I screamed at him, my voice rising to a sibilant, glass breaking pitch, “I think you’re actually jealous, because while you’re stuck in that swamp of junk bonds and semi-fraudulent securities, I’m trying to do something important with the rest of my life.”

Bill waited impassively through the end of my tirade. “I know this is important to you, Edward,” he said. “I respect what you’re trying to do, and I wish you well. I really do. It’s just that maybe I can give you a helpful perspective from the other side, as it were. And as I think about it, what I’m trying to convey to you is that people in every kind of minority spend so much time thinking about the group they belong to, they wind up believing that everyone else is thinking about it all the time too, and if they don’t talk about it all the time like you do, then they must be suppressing something, or hiding something, or avoiding something. The dull truth is that dull, white, middle class guys like me spend hardly any time thinking about the lives of gays, or blacks, or women. Since we’re not gays or blacks or women, we spend most of our time thinking about what we’re going to do today and maybe what we’d like to accomplish next. So when you show me some scene with gay pilgrims or George Washington in drag, I don’t find it very convincing, that’s all. But you’re the writer. You’ll work it out somehow.”

After he left, I pouted for a while. Maybe there was something in what he said. Maybe. But then why had I seen that sudden rascal light in his eye that day when I accidentally came to work with the previous night’s mascara still in place? No. I knew my mission. I was going to blow the roof off the whole heterosexual lie before I died. That would at least make my death mean something. My death. Oh damn. That again. Frantically I sat back down at the word processor and … Arma virumque cano Troiae qui primus ab oris Laviniamque venit. Multa ille terris iactatis et alto. Dux femina facta. Forsan et haec olim meminisse iuvabit.

We could leave it there, perhaps, but it seems kind of unsatisfying, doesn’t it?

UPDATE YEARS LATER…

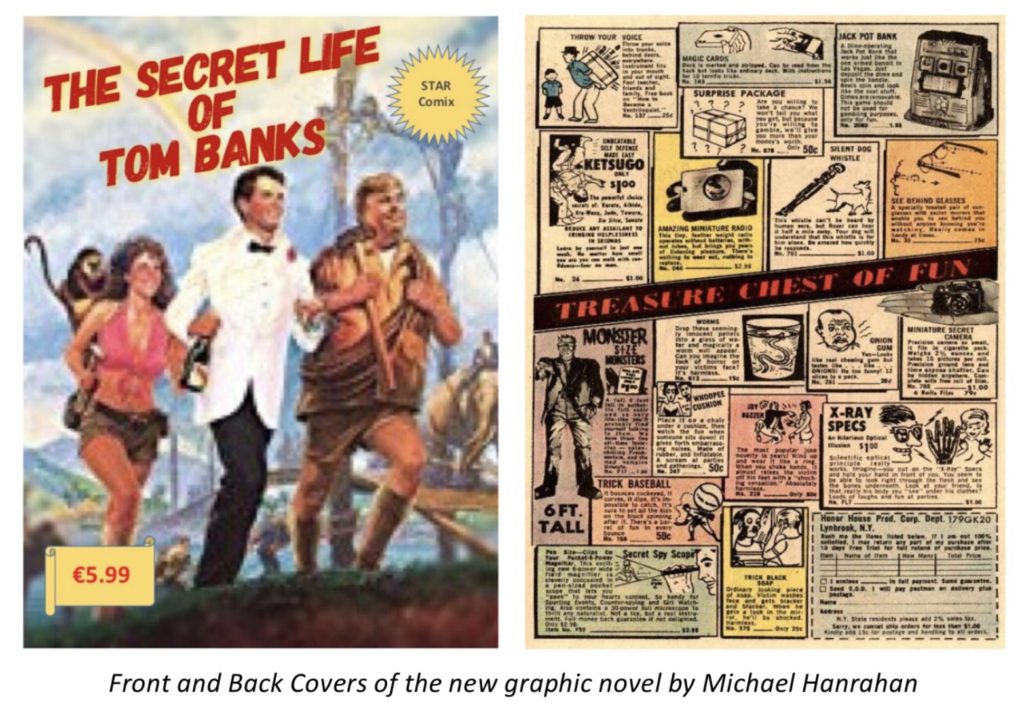

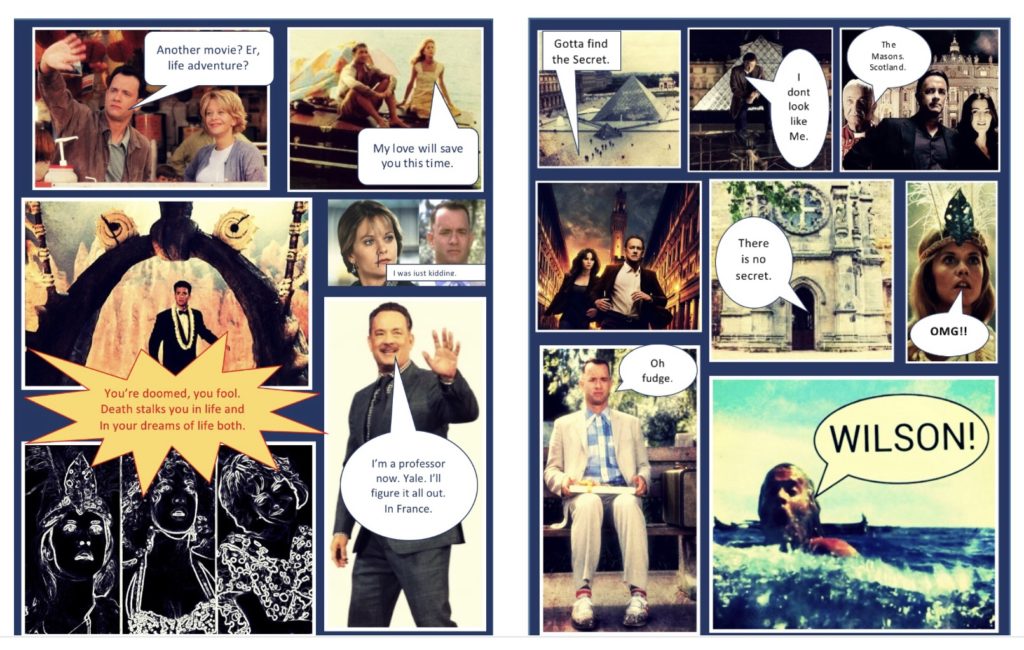

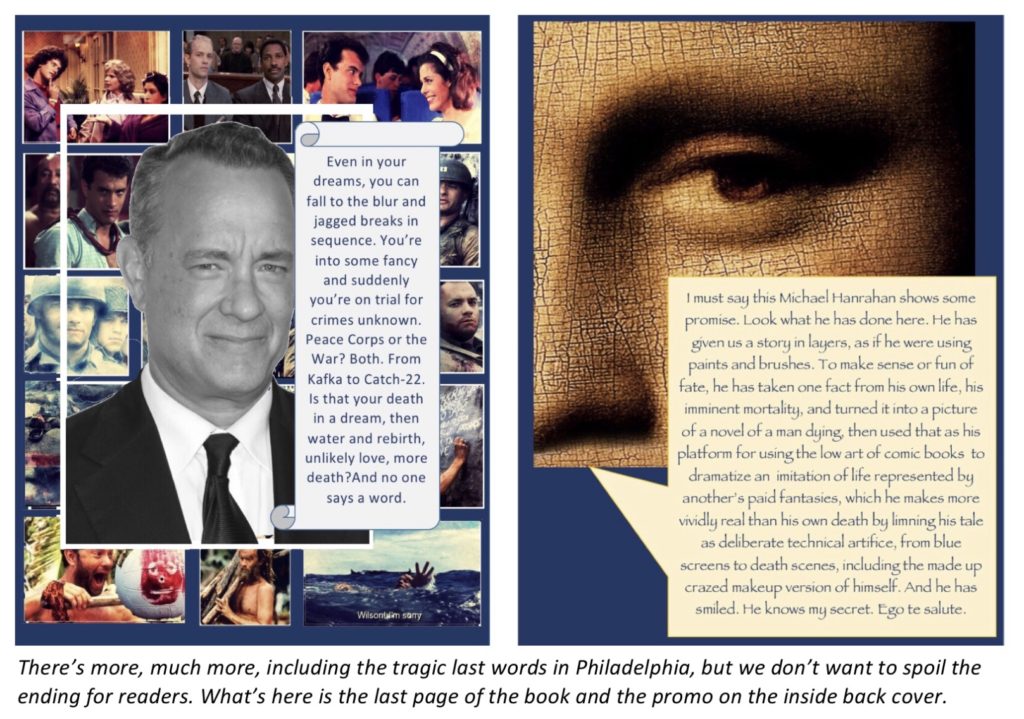

There was a second Hanrahan novel, this time an ambitious work in the graphic genre. In it he addressed his pain not just about death but about the difficulty of getting noticed in this world no matter who you are and how brilliantly you do what you do. It’s called “The Secret Life of Tom Banks” and we’ve excerpted it here for you as a bonus.

We certainly wouldn’t presume to improve on a review blurb by the great Leonardo Di Capuleti… or whoever.

Bye now.