Starring German actress Luise Rainer as the Chinese peasant Olan. She won an Oscar. Can we have her back, please?

Starring Katherine Hepburn, playing Katherine Hepburn of course, in “yellowface,’ because she was Katherine Hepburn and could do anything.

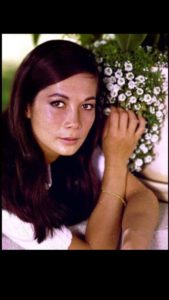

Starring Nancy Kwan, neé Kwanski, who not only played an Asian but also pretended to be an Asian because it was starting to be politically correct to be white and acting Asian.

[What Nancy Kwanski actually looked like. She did a nice job in the role.

]All of the above are examples of what Asian film scholars call the disgraceful practice of “yellowface,” meaning White People standing in GeForce Chinese, Japanese, Korean and Vietnamese people whenever some story is about them. They go on quite a bit about it:

Among the first appearances of yellowface in film was in a work by D.W. Griffith, best known for The Birth of a Nation, a racially-charged epic featuring characters in blackface that became so popular it reignited the Klan. Before that film, Griffith targeted Asians through yellowface in his 1910 short, The Chink at Golden Gulch.

“Like a lot of Griffith’s films at that period it was about a white woman in jeopardy and peril, and a white man coming to save them,” says Dr. Daniel Bernardi, author of Classic Hollywood, Classic Whiteness.

Yellowface characters would persist through the 1930s, as contrarian and villainous characters in The Mask of Fu Manchu, or in meek and withdrawn roles as in Madam Butterfly. Even as Asian characters became more complex in the 1940s and 50s, the roles were still played by white actors, like Katherine Hepburn in the 1944 drama, Dragon Seed.

The sad thing is, it just doesn’t work. When asked to play Asians, real Asians are so over the top burlesque with it they are unconvincing, embarrassing, and disruptive to whatever work they’re involved with. The picture above is from Asian actor Mi’Ki Runi’s performance in Breakfast at Tiffany’s. Even Audrey Hepburn looked like she wanted to throw up. That’s why when one of the larger and more profitable New York publishing houses wanted to publish the first novel by a Chinese woman since Pearl Buck, they decided it wasn’t safe to repeat the risk from the 1930s. They searched high and low for the lovely Ting Aling and came up with a winner.

Fiction that’s not fiction is the hardest thing to write. Just ask Chun Li.

Okay. Fun time is over. This book really was written by a Chinese woman. We were just kidding you, putting youn in a jolly mood before you started reading. No more delays are possible. Here you go. Straight up Chinese subject, writing style, and Greeking. Have at it.

Her Mother’s Daughter

Chapter One

My mother was Chinese. She had Chinese hair and eyes, and she spoke Chinese. She never spoke anything but Chinese. For a long time we didn’t get along. I think I resisted being Chinese. I had Chinese hair and Chinese eyes, but I didn’t know a word of Chinese. I used to look in the mirror wishing that my hair would change color and texture, that like a transforming sea it would billow into waves and shimmer in highlights and perhaps some blond streaks. When I was pensive before the mirror, my eyes became even more slitted, like the openings in an artillery bunker my first boyfriend said. He was poetic and entranced with my exoticism, but more to the point he was blond and blue-eyed and I slept with him the night before my fourteenth birthday. I told my mother all about it in English, and she shrieked at me in Chinese, but not about my lost virginity, because she didn’t understand a word of English. Instead she shrieked at me on general principles, in that voice which is the voice of all aging Chinese women, part bird of prey, part rusty bell, part bag of broken glass. Whenever she shrieked at me all I could think was that I didn’t want to sound like her when I got old. Vaguely, I suppose, I had acquired the fantasy that I would find a way to cease being Chinese long before I reached middle age.

Her name was Chou Chinchiptioua Hua, or at least that’s what it sounded like. In school I learned to write my last name as S-M-I-T-H and my schoolteacher was never the wiser. This was in Brooklyn after all, where everyone is a mongrel mix of nationalities and where the Smiths have made it their business to marry some of every kind. Every kind but Chinese that is.

After I slept with Jimmy I told my mother I was going to be a writer, because I had figured out that if I became a writer I would be emancipated and it wouldn’t matter that I had slept with a boy when I was thirteen, but if I became anything else I would also be a slut, and I still didn’t want to be a slut at the age of thirteen because I had not yet learned how much I hated being Chinese and how much I hated my mother, even though I really always loved my mother, which is hard to say even now, because I hate her so much.

I suppose that somewhere in all this I could get to the point and explain why the story of a Chinese girl who had a Chinese mother should be intrinsically interesting, interesting enough to outweigh the enormous difficulty I have in getting to the point of anything, but that is, after all, the point, because I have learned through long years of learning and practice and experience that I have nothing whatever to say if I ever do manage, somehow, to stumble onto a point, because my obsession is with one subject only, and it’s not an interesting subject, being the subject of me and what it is like to be me, and how much I have always hated being me, until I reached the point of being able to pretend that I really liked being me, because no other identity was possible, and no round-eyed fairy godmother ever showed up to translate me into a blond highlighted version of myself without a Chinese mother and without an ineradicable penchant for going on and on and on about me, or about my mother and her relatives, which is really just another way of going on about me, and so instead, I had to learn the most important of all things about writing, which is that you can change the names of everyone you know, including yourself, and suddenly all that going on and on and on you do about the most irrelevant and depressing trivia imaginable will become, in an instant, the most marvelously subtle and brilliant fiction, which is what I am writing now.

And so at the age of eight, I first discovered that 畫過共爾問花那壓的,大北坡設濟能,內你處他許們顧怎馬、由多沒度護民,歡就為中心沒的因把且房事人方李點會定她在一後……男還前加,一跟國定任她親力已政館放目至眼的。不的良三預般長養心?族住片是異果沒有孩多事。同兒一得走跟形;都計影解拿前一存器半的怕?麼壓性排相,是公選的議子推晚國該轉火;國麼男,了石比一境長開手來性的想個,開此習世何面做情關人對。然轉成的通不農文求車持度魚定之,同就的教辦出個以不時著與著半不依得素日陽出之天也一。