Call this the tale of a Love Game.

Responding to a 6-0, 6-0 victor today on the most aristocratic court in sport:

Let me tell you a tennis story. Just so you know where I’m coming from. My dad was not rich but he was a tennis fanatic. We had an old property in rural New Jersey and my dad decided to turn a small adjoining field into a tennis court. We did it together. I was eleven. A neighboring farmer’s tractor plowed it even, we staked out the dimensions with string, and then we set the posts one by one for the fencing. He with the posthole digger, eighteen inches deep ten feet apart, me balancing the rough timbers while he filled and tamped. Next, chicken wire. Hammered into the posts with copper staples while he held the wire as taut as he could. His hands bled. I had never played a lick of tennis.

All day for every day of his vacation and countless weekends. We mixed concrete to set the net posts. We painted them green, the caps silver. All done?

No. The roller, from his father’s old tennis court, three feet in diameter filled with water, handles rusty from sitting for 30 years. It weighed a ton. We were recreating a court on which my father had learned all his earliest lessons about competition and fair play. Didn’t learn for years that he had once taken a swing at his own dad on that tennis court and gotten decked for his temper. The hell he was putting me through was actually all for me. He wanted me to have that same advantage.

So. The roller, the rake, the brush, everything it takes to turn clay into a playable surface. And the old-as-the-roller line bucket trolley, filled with lime water which has to be rolled along engineered vectors to keep the court lines true.

It became part of my chores, in addition to mowing two acres of grass, clearing the plates after dinner, and weeding the front terrace. I’m not complaining. I took pride in the lawn and the terrace, I liked helping my mother since my sister had the job of setting the table, and when we actually finished the court, I was introduced to a new world. I was put in whites, given a catgut-strung racket, and introduced to the game of tennis.

I had talent. My forehand was ferocious, sometimes so hard my father, who was still struggling to regain a game he hadn’t played since the war, found it hard to return. I was good enough that a coach was hired, and he told me I could go all the way, or if I didn’t want to, I could still be the best country club player for miles around.

We practiced at home and became members of a local country club where my coach was the pro and my parents had friends. I played and beat kids several years older than me. I was honored by being named a ballboy for an exhibition match between Davis Cup champions Chuck McKinley and Vic Seixas. I was going to be a tennis player. But then something happened. Not a big thing, I guess. But enough.

My parents, not rich as I said, nevertheless rubbed shoulders with the rich and even the very rich. Truth is, my dad didn’t need to build a tennis court at all. We had friends less than a mile away with a har-tru tennis court whose cyclone fencing had green canvas clothing. There was also an adjoining Olympic sized swimming pool and brick bathhouse where all friends were welcome to swim and play. And everyone did. Where I learned social conventions about winning and losing. Don’t use your hardest forehand against your parents’ female friends in mixed doubles. Don’t ogle the doctor’s faithless wife who has spent so many hours sunbathing that she’s literally made of leather — even when she accidentally drops her top in front of boys a fourth her age. Manners, we were told.

There were parties there. Huge liquid affairs. Lobsters, clambakes, pool parties, Swedish models who caused upsets we weren’t supposed to know about. Meanwhile, the roller, the rake, the brush, the lawn mower, and cedar thorns in my hands from weeding the terrace. I was exposed to these people on a regular basis, but I was expected to know better, be better. Why? Without ever a moment’s explanation of the contradictions or the issues involved. It was all just a matter of manners and our impeccable surname. Period. I do my chores without complaining, I ask no rude questions, never inquire into the behavior of the elders who were my parents’ friends, and that would make me a good boy.

But, as I said, something happened. One of my father’s friends, from college not the place down the road though they were sometimes there, was the sole heir of the Dow Chemical Corporation. He was the CEO, on top of the world, with a beautiful wife and child and everything to live for. He was, as my dimming memory suggests, headed somewhere for a Thanksgiving meeting with his beautiful wife, in the private plane he flew, another bond he had with my pilot father. But he crashed and died along with their four year old daughter, and their lives were just wiped off the map.

She, the beautiful wife, just disappeared. No more parties, no more appearances in public at all. My impression is that the lovely rich people were afraid to call her or didn’t know what to do about her, and she became a ghost, mentioned in sorrowful tones but never with any information. What do you say to a woman who has lost everything?

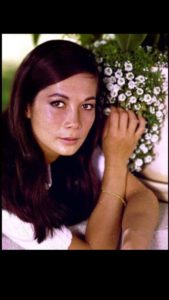

Then, suddenly, my father announced that Alice Dowes was coming to play tennis tomorrow, and we rolled and raked and brushed and rolled and relined the court, and she came in her tennis whites, and she played tennis with my father, who played better than he almost ever did because he didn’t want to unmask the camouflage of the game. I watched. She was still lovely but ravaged looking, her face lined and drawn though her legs were still lean and strong.

As I remember her. Almost exactly. Half a century later. Reminds me of… Same mien.

She had a potent forehand and I’m not sure they did anything but hit them around. Then she had a drink on the crabgrass apron of the court and left. My parents shook their heads at one another. They had tried. They had reached out and done their best. She had come. She had tried. But there was nothing anyone or anything could do.

I’ve thought of this scene again and again over the years. This multi-multi-millionaire widow who could be playing tennis if that’s what she wanted in every glamorous spa in the world, playing not quite tennis in our field court with its chicken wire and rough-hewn posts. Why had she come? Because my parents asked and she was lonely? Because she wanted away from the invulnerable moneyed class? Because she wanted to lace into a tennis ball with no one watching who mattered a damn, no one who would interpret her behavior and try to play it?

I never became as good at tennis as my coach had hoped. I excelled for a while but I developed in my high school years a hitch in my once deadly forehand that only in latter years have I come to recognize as what golfers call the yips. Just before the ball strike, there was a quiver, tiny but fatal. Suddenly you’re no good at the game at all.

The yips. Connection? I won’t offer one. Despite my father’s hopes, tennis was never the great life lesson he had worked so hard for it to be for me. Not his fault. It was a game, a sport, but not a life. Being good at it would never be enough for the cost it would exact for trying to be great at it. I fenced saber for a time. Same thing. Why I moved on to words.

Mind, I started from the same place. In a plowed, fallow field with a post hole digger and rough timber, chicken wire, a rusty roller, a rake, a brush, and more chores to do. And an image of tennis whites against a background of black.