January 16, 2009

A miracle? Maybe.

SMIRKS AHOY. It always makes me nervous when people start tossing around the term “miracle.” Not because I don’t believe they ever happen, but because I can feel the insipid grin of the disbelievers, waiting for any opportunity to restate for the umpty-umpth time the threadbare objection, “Why do bad things happen to good people?” Every purported miracle is, to them, a reminder of all the miracles that somehow didn’t occur somewhere else at some other time.

I hate that grin and all the arrogant banality which congratulates itself on knowing the physics of a universe honest physicists know they don’t, and maybe can’t, fully comprehend. So I’m going to risk the scorn and ridicule of the sophists by proposing an analogy that may help others consider a new way of thinking about the “bad things happen to good people” objection.

In the grand scheme of things, miracles are pretty rare. That is, the kinds of events which even people who believe in them might call miracles are rare. When you think about it, rarity is built into the definition. If every bad thing that threatened to occur were somehow prevented or reversed after the fact (like sudden total remissions from terminal cancer), the outcomes wouldn’t be considered miracles. They’d just be the way things work. Miracles are an exception. OR they are subject to particular conditions which are hard to bring about, especially since we don’t have much of an idea about what those conditions might be. For example, winning the Powerball lottery is an incredible long shot that nevertheless does occur; however, it does have an unavoidable pre-condition. You must first purchase a Powerball ticket.

On to my analogy. From time immemorial divinity has been closely associated with lightning. Zeus, Jove, Jupiter, and even the Bible’s Yahweh have been associated with lightning bolts, and there’s no mystery about why. It’s an ipso facto perfect symbol of a power from above visibly impacting the earth (and its inhabitants) below. Lightning strikes are pretty common events. Fatal lightning strikes on individual people are less so. That power from above is more or less always there. Its direct connection with human beings is limited by certain pre-conditions. People who know better than to wander around out in the open during a thunderstorm are not likely to be struck. And, generally speaking, lightning is more likely to strike big tall things like trees and church steeples rather than little things like people. But why does lightning strike tall things? Repeatedly. Which it does. Does it know that the tall things are there? And if it doesn’t, why wouldn’t it just strike randomly all over the place until it happened to connect with something it can light up? Why does it strike the tree more often than the outstandingly conductive bronze lawn ornament 24 inches off the ground?

Why? Because a lightning strike is a two-way process. The lightning bolt reaches down from the sky, and prospective targets on the ground reach up. They send out what are called streamers, which meet up with the lightning bolt and establish a connection. Here are two photos of streamers.

Connection made.

Connection sought.

The streamer is, in our analogy, a pre-condition. It’s the act of buying the Powerball ticket. And it helps to be a tall tree or a church steeple or a steel water tower at the center of town when a thunderstorm is in the air.

All of which is a fancy way of saying that miracles may, in fact, be precipitated by their recipients. Not through goodness or virtue alone but because they are also associated with preparedness, mass of some sort, and the kind of sharp focus we see in the streamer photographs.

That’s what’s so cool about the so-called Miracle of the Hudson. We can actually see a confluence of circumstances that apparently, luckily, resulted in — but just possibly catalyzed — an incredibly unlikely outcome. A variety of fortunate circumstances cannot explain away the improbability of the outcome, however much we want to play games with odds and statistics. The fact is, commercial airliners without engines “fly” with as much lift as a falling boulder, and they, well, effectively never land with wings straight and level on the water.

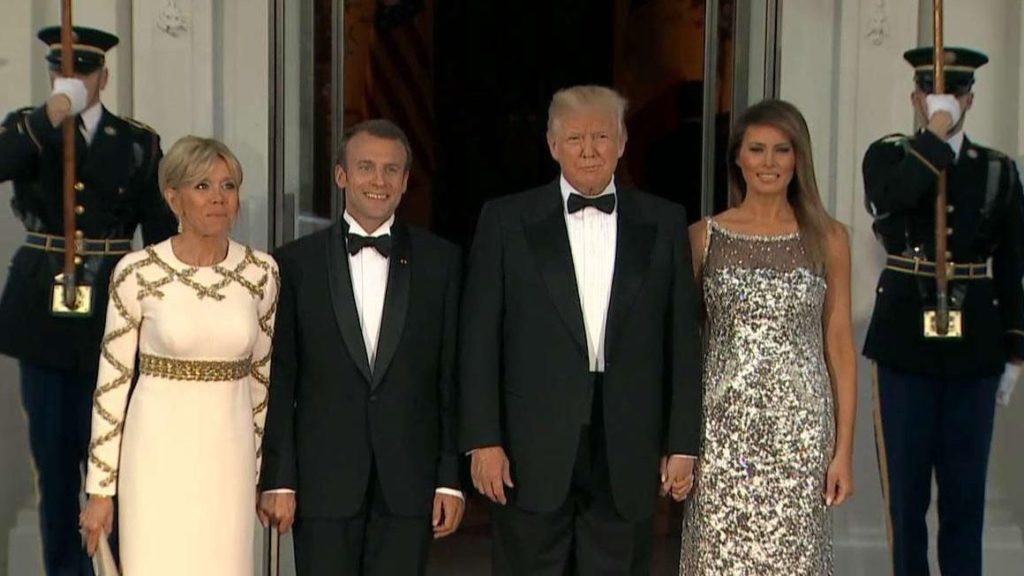

But in this case there were streamers. A pilot who was not only skilled but learned in the split-second differentials of commercial air disasters, who had made a long academic and practical study of air safety under emergency conditions, and who (to be frivolous for a moment) bears a striking resemblance to Douglas Fairbanks, Jr.

Captain Sully of Flight 1549 and Douglas Fairbanks, Jr. (Commander

Fairbanks’s uniform is real btw. He won the Silver Star in WWII.)

He was sending up a streamer. As were the ferry crews and FDNY personnel who responded so swiftly, as well as the passengers who quelled their impulse to panic and responded to the ancient call, “women and children first.” Preparation, determination, and cool heads with a fervent desire to do the right thing are all streamers, and there was mass behind the entire effort. The lightning bolt that could have remained in the clouds reached down to make a connection, and the incredibly (impossibly?) unlikely outcome occurred.

Just an analogy. Not even a theory. But if we follow the analogy, we can also glimpse the possibility that just as lightning bolts are chaotic things, so might be miracles. In my own mind, the collapse of the Twin Towers was a miracle for its relatively low loss of life. It could have been upwards of 20,000, as many surmised it was in the darkest hours of 9/11. But how many brilliantly bright streamers went up that day, from firefighters and policemen and gravely unselfish civilians, to connect with the lightning that brought so many thousands of people to safety? I know the grinners would cite that day as a miracle that didn’t happen. But you have to remember that they live in an irretrievably drab world of actuarial tables and lottery tickets that win nothing but heartache and ruin.

But when their turn in the storm comes, they too will pray for a miracle. And they might even receive it — if they’re prepared, focused, and united in unselfish resolve.

– posted at 5:27 pm by CountryPunk Permalink