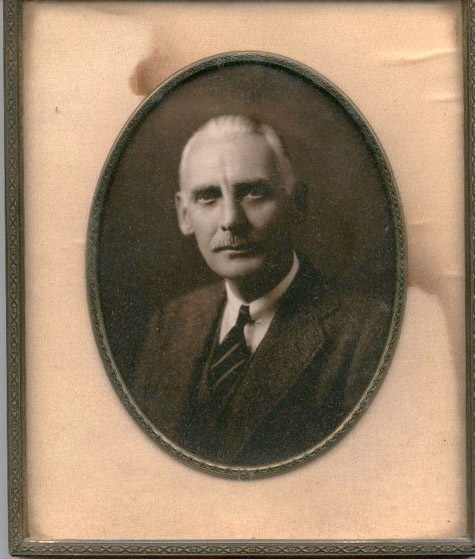

My dad painted her from a daguerreotype..

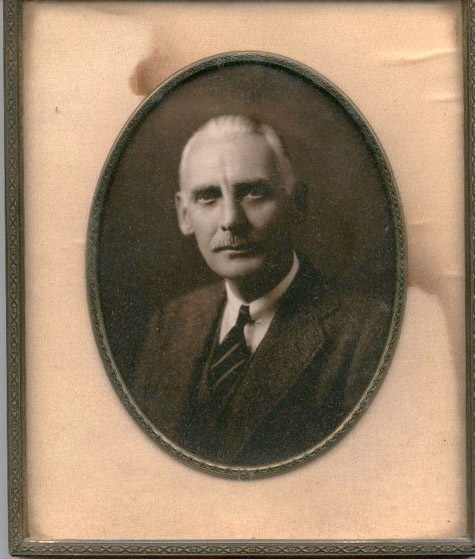

I don’t even have a photograph of him anymore. The most important person in my life. My paternal grandfather. Boppa.

Getting ahead of myself here, as usual. Listening to Limbaugh today reminded me. He was observing some anniversary of his relationship with his grandfather, the lawyer patriarch from whom he gets his name. Yeah. Limbaugh is a numeral III, just like me.

In all the years, I’ve never talked about Boppa much. He was the original rflaird. He’s a writing challenge I’ve never been up to. Just telling the facts sounds like you’re repeating exaggerated family mythology. So you just don’t say anything instead.

When I met him, he was 64 going on dead. He’d had skin cancer on his back. They prescribed radiology treatment. A doctor left him under the beam too long. Way too long. It burned a hole in his back the size of a man’s fist. His backbone was exposed. A wound that could never heal. It had to be cleaned and dressed and bandaged every day for the rest of his life.

When he did finally die at age 82, his surgeon and chief medical attendant, a man most regarded as a shallow, materialistic jerk, broke down and cried. “You’ll never know,” he said, “how much pain that man was in every single moment of his life.” He was the one who had the job of picking decaying fragments of bone from Boppa’s continually open wound.

As a child, all I knew was that Boppa’s back was off limits. But he was still a great grandfather. He was the picture perfect grandfather of movies, children’s lit, and TV, endlessly patient, wise, funny, and, yes, handsome. His hair was Snow White — had been, mysteriously, since the age of 21 — and he had a close clipped mustache just as white.

He was also dapper. Despite his wound, he put on a suit and tie every day. He walked with a cane, not because he was feeble but because any fall would be a disaster. He made it a personal accent. Once he ran off a thug who was assaulting a woman by brandishing that cane on a sidewalk of Salem. Family said, “Boppa, how could you?” He said, “I just did what I could.”

Oh. The name. Two children. My dad and his sister. She had kids first. The eldest of hers couldn’t say grandpa. It came out Boppa. All six of his grandchildren called him Boppa from then on.

There was a twinkle in his eye. Thing is, he was pretty much of a superhero. There’s no other good explanation for how you can keep on living and thriving with the kind of injury he sustained. (No. He didn’t sue. He forgave the radiologist his error.)

Why I haven’t written much. The facts of his life come off too much like the backstory of a graphic novel. He was that extraordinary. He was the second youngest of six sons. His father wanted him to take over the family’s million dollar business of shoe manufacturing. Boppa said no. He was a chemist by trade and he launched one of the first sulphur dyeing businesses in the United States. He was pulling in $50,000 a week when WWI started and a German chemist in his employ burned the whole plant to the ground.

Declare bankruptcy and get on with it, right? No. Boppa repaid every creditor in full. It took him almost to his retirement from duPont to do that. Yes, he was a top chemist at duPont. He was a troubleshooter. You have a dangerous problem? We send in rflaird. A lead ethyl plant during WWII. Something went wrong. Boppa evacuated the plant immediately and went in alone to shut down the process.

In those days, lead ethyl poisoning was 100 percent fatal. Insanity followed by death. Boppa finished his job, drove home, and went insane. He was crouched in a closet, waving a gun, when his equally brilliant brother, a Philadelphia society doctor, arrived with his own unique concoction to cure his little brother after a high speed chase that got him from Philly to Salem in 45 minutes.

Improbable, eh? Why I haven’t written much about these dead titans. Except that I’ve been myself the beneficiary of the superhero doctor of the story.

You see, I got bitten in the face by a dog when I was eight. I scar malignantly. A registered nurse at the scene warned my mother that I would be scarred for life across my nose and cheek. So we trundled home and my mother pulled out the last bottle anywhere of my great uncle John’s salve called Arkase. She applied it every day and the nurse nearly dropped her teeth when she saw me a month later with no sign of a scar.

I know. Family stories aren’t supposed to be true. But what do you do when they are? The story of my grandfather’s back is absolutely true and it’s the most dire of them all. We spent a lot of time together because my sister had eye problems and went regularly to Camden and Philly with my mother and Grandma. That left Boppa and me alone together. We talked. He didn’t treat me like an idiot child. He approached me as if I were an intelligent person who didn’t know that much yet.

The end of stories like this is grim. I got sent off to prep school when I was thirteen. At Spring Break I came home, just as Boppa was going into the hospital. I saw him off, but my parents didn’t want me to visit him. They insisted, demanded, forbade me. I insisted, demanded, and won. But they had been right.

To this day I cannot clearly recollect what I saw in that hospital bed. Within the space of 24 hours, all the ravages of pain and suffering my Boppa had withstood for twenty years descended. What I saw was an ancient, barely living fossil, on his back.

I shouldn’t have gone to the hospital. That night, I was the one who heard the phone ring. I woke my dad, though he told me later I didn’t, that his dad had come to him first to say goodbye.

A comforting lie to a son? Well, maybe. But I had my own moment. I went to the third floor of Boppa’s house the day of the funeral — funerals have never done much for me — and I was looking down on the yard when I felt Boppa with me. (This is no writing trick. I teared up as I was writing that.) we had a brief communion. I promised him I would be a good boy. I failed to keep my promise, but I made it sincerely on that day.

Already gone on too long. Never told you about the role Boppa played in my more than excellent education. Or the example he set with his impalement on a wrought iron fence when he was five… Yes, he still had a scar.

But leave that for another day. What’s left? The portrait of Boppa’s mother above. She died when he was four. My dad painted the picture from a picture. All Boppa had was a dream of himself and his mother on a train. He could see her hand and that’s all he had left of her in his life.

Boppa. It took my wife to remind me this pic still existed.

They’re all gone now. My father, my mother, all my grandparents, all our dogs and cats. I wish they all wanted to greet me. But I fear I’ve gone too far. Also, I had a dream about Boppa when I was in my thirties. I was trying SO HARD to reach him, but he was already busy with a new life. “You don’t need me anymore,” he said. He was a doctor this time, and funny looking. Kindest thing any dead relative has ever done for me.

Know what? I don’t believe it. Boppa was just giving me a vote of confidence. Hardly anyone has ever done that.